It’s 2015, I’m a twenty-something-year-old and somehow, I’ve never had an account on any social networking sites…until now. Did I live in a cave all these years?

Like other privacy activists, many considered me paranoid for years – and in some ways, perhaps rightfully so. After all, unlike my peers, I never had a Facebook account. I never had an account on MySpace, Twitter, or on any other social networking site for that matter. Somehow, not even my global nomadic lifestyle over the last years has not been a strong enough incentive to get me connected on social media. Why? Well the idea that information about me would be owned by a corporation and available on a platform which would enable potentially anyone, anywhere around the world to view simply freaked me out.

by bark on flickr

Would I tell random strangers my address? No. Would I tell them who my friends are? No. Would I share my personal pictures with them? Hell no. And handing over all this information for free to a corporation which, in turn, would sell it to multiple other parties without my knowledge or informed consent simply did not make any sense to me. As a result, I spent all of my life (until now) being the weirdo who’s not on Facebook or any other social networking site. And in no way have I regretted or re-considered joining platforms like Facebook. Twitter, though, is quite an interesting case, I think.

Many privacy activists today – if not most – have accounts on Twitter. For quite a while, this struck me as a huge paradox and here are some reasons why:

1. Like other social networking sites, Twitter makes money out of our data

2. Twitter shares, sells and discloses datasets to multiple, unknown third parties

3. If users don’t use anonymity software, like Tor, Twitter knows their geographical location

4. Twitter can potentially map out its users’ real-life social networks

5. Users’ tweets and retweets can show and map out their interests

6. Users’ tweets and retweets can show and map out their thoughts (and sometimes even their emotions)

7. Users’ retweets can show and map out who they likely follow and, hence, are interested in and/or are associated to

8. Analytics on Twitter datasets can show and predict how individuals and groups are likely to behave

9. Even though Twitter supports Do Not Track, Twitter is able to track most of our online activity anyway through the inclusion of its button in most websites

10. Every tweet is a public statement to the world – how easy is it to remember that across time?

by ItzaFineDay on flickr

The world is being digitised and, unfortunately, independent online public spaces for free speech on a global, mass level do not exist yet. Free speech and the free, uncensored sharing of and access to information is a vital component of any free society. However, the transition of societies from the offline to the online domain has been a challenge for all, and particularly for governments. Traditionally, governments have been considered the main actors that are responsible for responding to citizens’ needs. Over the last decades though (and arguably way longer than that), most governments around the world have failed to meet citizens’ needs adequately due to lack of resources, interests and various other reasons that I will not analyse in this blog.

Similarly to governments, corporations aim at responding to citizens’ needs. Unlike governments though who are supposed to serve the public interest, most corporations serve their own financial interests. When governments around the world failed to meet citizens’ need for an online space which would serve free speech and the free dissemination of information, corporations, like Twitter, jumped to serve – and profit out of – this need. As a result, Twitter has monopolised the online public sphere for free speech to mass audiences. And who can blame them? From a business perspective it makes sense and it only reflects governments’ incompetency when meeting the digital needs of their citizens.

But it’s important to remember that Twitter is a corporation and like most companies, financial profit is at the heart of its interests. And in some – if not most – cases, such interests might not serve public interests and the overall well-being of societies. After all, Twitter’s business model is largely based on advertising, which is supported through the segmentation and profiling of individuals and groups. Data segmentation can not only lead to social stratification, but also to social discrimination. While we might innocently tweet articles, news, throughts and ideas which we consider to be important to the world, an entire data industry is aggregating our data, matching patterns and creating profiles about us – which may or may not be accurate. Regardless, if algorithms determine that we belong to a specific data segment, various actors (advertisers, insurance companies, banks and maybe even governments) take decisions which might influence our lives in direct and/or indirect ways.

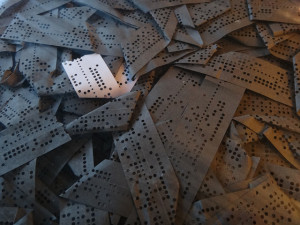

by Tom Woodward on flickr

Most of this happens behind the scenes. The architecture of the internet is designed in a way which prevents us from knowing which specific parties are collecting and aggregating our data in any given moment. When we access websites, for example, various companies are tracking our online activity through the use of cookies and other tracking technologies. They then subsequently share this data with other parties, who in turn share it with others, and the chain of third party actors who ultimately gain access to our data appears to be quite endless. No doubt, one these actors is Twitter and a project I work on (“Trackography”) shows that it is one of the top 5 companies globally which track individuals’ online activity the most. So why support a tracker by joining its social networking site? Why support an actor which spies on citizens’ lives for a living?

by Marines on flickr

Twitter can be very empowering. In fact, it can arguably empower citizens in ways that most governments throughout history have not. After all, when have citizens in the past had the opportunity to instantly and independently express their opinions and ideas to the world…at the click of a button? When have citizens in the past had the opportunity to choose the types of news from around the world that they want to read and to receive such information instantly, all in one platform? When have citizens around the world had the opportunity to instantly find and connect with other citizens who share the same passions and interests? No doubt, Twitter can be extremely empowering…but it can also be quite dangerous.

When we have the power to instantly make public statements to the world, we also have the power to instantly expose ourselves to the world. Publications on more traditional platforms, like newspapers, magazines or journals, have a subtle advantage: they require an editorial process prior to publication. The fact that we can instantly and independently publish on Twitter deprives us from this editorial process, which means that we probably do not have the time and/or resources to review, proof-read, edit and gain feedback for everything we publish. In other words, the fact that no editorial process is required prior to publishing on Twitter means that there is a high probability that we will publish things that we might later on regret.

Recently I edited an article that I wrote for Tactical Tech a year ago. Back then, I was quite pleased with my article. When I revisited it a few days ago so that it can get published soon, I was horrified by it. I view the topic from a completely different lens now and I was surprised by the amount of conclusions I jumped to, the important information I somehow failed to include and the various inaccurancies througout the article. I could go on and on about this, but my point is that in the end of the day, I am very thankful for the fact that Tactical Tech has a set of individuals which can provide me feedback, challenge my assumptions and help me review my article before it gets published to the world.

Twitter, though, does not have this advantage, but that might not necessarily be a problem per se. After all, we’re humans and our thoughts, opinions and ideas are bound to change across time anyway, regardless of where they get published, right? But when we think along these lines, we likely forget that Twitter is not just a publisher; it’s also a data mining engine which can correlate our publications across time and match them with specific groups and individuals within networks. And then that brings us to the following question: how long will our Twitter data be retained for?

by Nick Sherman on flickr

According to Twitter’s privacy policy, it only retains data for up to 37 days once an account has been deleted. However, let’s not forget that Twitter – like many other corporations in the data business – shares, discloses and sells data to multiple other parties, all of which have completely different data retention periods. So while Twitter might indeed only retain our past tweets for up to 37 days after we have deleted our accounts, how long do all the other third parties retain our Twitter data for? I think it’s quite difficult – if not impossible – to answer this question.

In addition to data retention concerns, Twitter also fosters citizen-consented tracking on steroids. Multiple companies in the advertising business generally tend to embed tracking technologies, such as cookies, in websites to track individuals’ online activity and interests. Twitter though appears to be at the frontline of innovation, since it does not necessarily need to rely on actively tracking individuals: its users do all the work. By having a Twitter account, we pretty much provide Twitter (and the world) a lot of the data that many companies would otherwise have to dig out through the use of tracking technologies. Anyone can potentially map out the types of media websites that specific people read, the news that they are interested in, their political beliefs and ideologies and much more through their tweets. In short, most of what tracking technologies are designed to collect is actually being donated to Twitter by its users.

by Seth Anderson on flickr

Data mining and profiling can raise serious concerns – especially for those placed in vulnerable positions within societies. Would it be ideal for governments to be able to map out all of the political activists within their countries? And would it be ideal for governments to not only be able to map out activists, but to also be able to map out their networks and associations? Interestingly enough, Twitter’s privacy policy states that “non-personal information” that it can share or disclose includes the people that we follow and who follow us on Twitter. Given that the specific third parties which Twitter shares data with remain quite opaque, in theory this could mean that the social networks (followers) of activists could be shared with oppressive governments for all we know. The business model of Twitter (and the internet at large) is such that the probability for breach appears to be high, while safeguards for human rights appear to be inadequate.

And as if all the above concerns are not enough, I’ve also been told far too many times that a really bad trolling culture exists on Twitter – which I guess sort of inevitably comes along with free speech to some extent.

by Anna Bialkowska on flickr

Nonetheless, I finally decided to create a Twitter account under my real name. This probably sounds like quite a schizophrenic decision – given my argumentation in this article – and perhaps it is. But it generally derives from my overall – arguably naive – belief that public awareness and mobilisation is a key component for structural change. More importantly though, it comes down to one main thing: I care a lot about freedom (probably more than what’s good for me) and I desperately want my voice to be heard.

Is this a wise trade-off though? Is it wise to donate some of my interests, networks and other valuable data to a corporation – which is not transparent about all the parties it will subsequently share my data with – in exchange for free speech on a global, public platform? To be honest, I don’t know. What I do know though is that it’s probably not fair to expect the public to mobilise against mass surveillance and other threats to human rights, without mobilising myself. Another thing I know is that those in power often foster fear within societies, which enables them to maintain and expand their power often at the cost of human rights.

Unfortunately it’s quite a chicken and egg situation.

On the one hand, if activists join social networks like Twitter, those in power can spy on them and their networks more effectively; but on the other hand, if activists don’t join such platforms, it’s very hard for them to mobilise the public and to get their voice heard.

The fact that the largest online public space for free speech is monopolised by a corporation is at the core of this problem. By no means am I suggesting that governments replace this role, as that would likely lead to even more severe concerns for abuse – especially in authoritarian regimes. What I am suggesting though is that we start creating autonomous online public spheres for free speech, which are free from corporate and government surveillance, and which can reach large and diverse audiences around the world. This of course is easier said than done and extremely complicated, but change won’t happen unless we aim to reach the impossible.

Until then…hello Twitter.